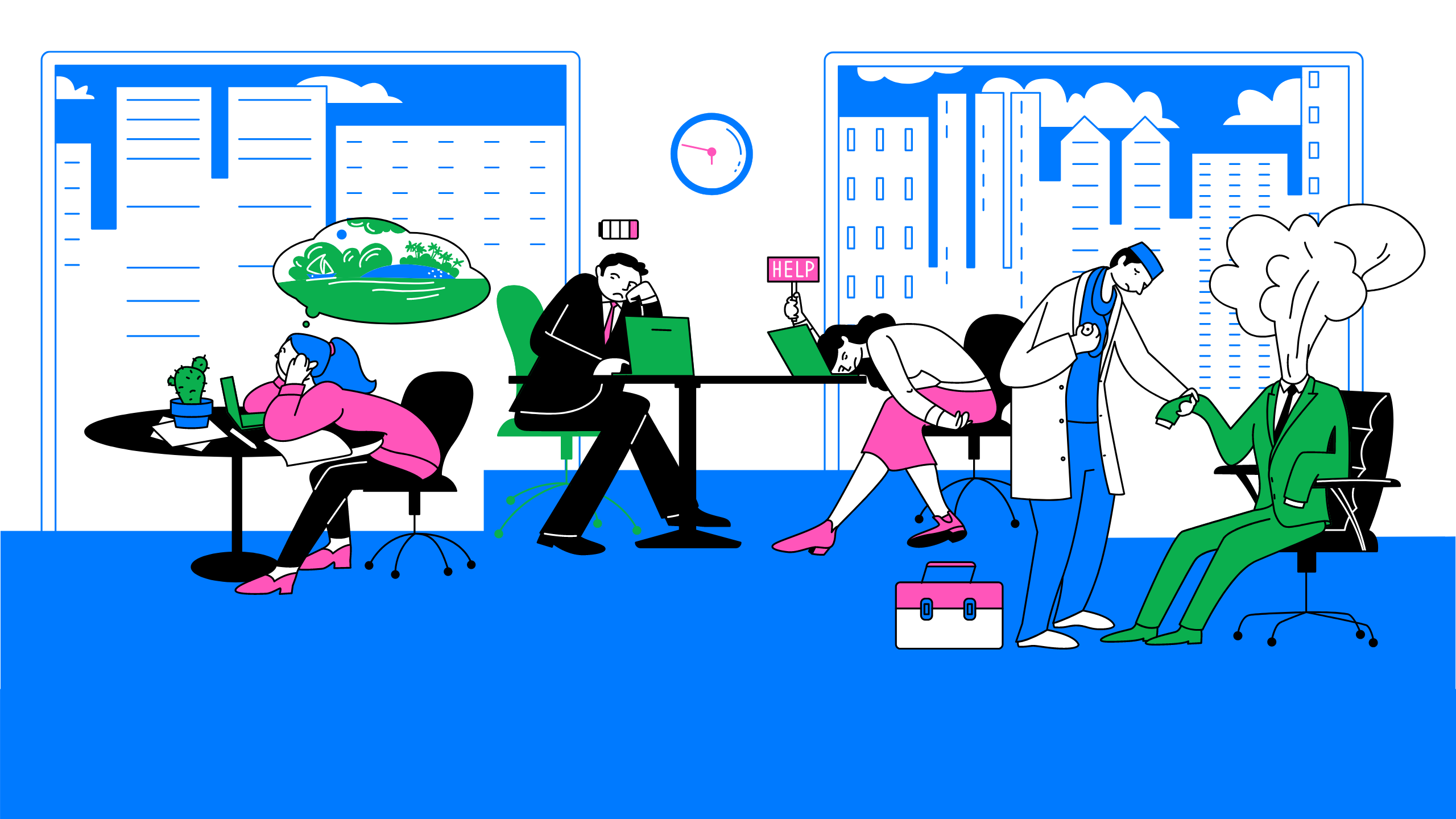

An Overlooked Solution For 'Virtual Event Fatigue'

There are countless articles, tweets, and LinkedIn posts from marketers and others expounding upon the future of virtual events and conferences; how ...

Hundreds of millions of people — including first-time users like college students, grade school kids, and tech-averse seniors — have been forced into daily use of videoconferencing by COVID.

At a high level, what we’ve learned is that although video communication is sometimes effective as an alternative to face-to-face, it is rarely satisfying and also fatiguing in large doses. And, it’s complicated. There are a number of overlapping problems, which I’ll go through here.

It’s easy to take the ability to move for granted. Even in the most militant real-life meeting, you can change seats, walk around and take a break, or just lean back, in, or slightly move your chair. Not so on Zoom. You are pinned in a tiny box with just room enough for your head. You can’t wiggle around. If you lean back in your chair you’ll be hard to see and/or hear. If you lean forward to better read your screen, you are showing everyone only your forehead. Maybe you want to sit next to a favorite teammate… nope, you can’t. You can’t move your little box, and they are positioned randomly — and worse yet — everyone sees a different mix of boxes. Like being at the zoo, but you are one of the animals.

Speaking of animals… A couple hundred million years ago, our eyes evolved to become whitish-colored with distinctive irises — making it easy to see exactly where other people were looking. This powerful change allowed us to better cooperate without sound, taking advantage of our big brains and intensely social nature. We remain the only animals to have evolved this advantage.

In a Zoom call, eye contact and more generally all signalling done using gaze direction is lost. Looking directly into the eyes of the other person now means that they see you looking away. This is because the camera (that is showing you to the other person) is not located in the same place as the other person’s eyes. In a group-call things are much worse. If person A looks in the direction of person B, person C sees person A looking at person D.

We have also been trained to interpret someone looking away from us as a bad thing — it means that they aren’t listening, disagree, feel uncomfortable, or are hiding something. And that's what you look like to someone the entire time on a Zoom call... unless you are one of those people who fakes it by looking right into the camera, which of course also means you now can’t see the person with whom you are communicating.

Another nail in the videoconference coffin is shown in a study done by Yale. Believe it or not, people perform better at understanding the emotional state of another person when they can only hear them, as compared to when they can both see and hear them. For many people and conditions, video actually reduces the quality of communication.

When you stand in a room full of people talking, you can do that weird thing where you focus your attention on just one conversation. You completely ignore the person blathering on in front of you about the election, while listening to that person over in the kitchen talking about your high school crush. Right? You know how that works? What happens is that your brain uses the direction and distance where a voice is coming from as a way of putting them each into little boxes that you can concentrate your attention on if you need to. On Zoom? So sad… all the voices are coming from the same place right inside your head. You can’t understand even two people if they talk at the same time, let alone have an old-fashioned pre-COVID party.

To fix this problem you need spatial audio, which processes each speaker’s voice in a special way to make it sound like it is coming from the direction of that person. This is very hard to do for multiple speakers at once, and there is only one company that has figured out how to do it for large groups (I’ll let you guess). Here is a demo of what a Zoom call would sound like with spatial audio. So this is something that can be fixed, and hopefully will be soon.

On a video or phone call, try this: start your stopwatch and immediately say "One", then the other person says "two" as soon as they hear you, then you say "three" when you hear them and so on until you hear "ten". Stop the clock. If it took more than 6 seconds, you are going to be interrupting each other and unhappy on the call because of the delay. That is because we pause ¼ of a second or so between sentences, so if the other person starts to speak, we can stop and let them. A six-second counting time means a one-way delay of ⅕ of a second. That much delay or more means you start the next sentence before you hear them start speaking.

To fix this, the software has to be optimized to get the one-way delay below ⅕ of a second. Zoom has actually done pretty good work in this regard — many Zoom calls are below the threshold (try it yourself and see). But if you are unhappy in a call, see if it takes 6 seconds to count together to 10.

Although they may be uncomfortable and look silly, believe it or not, wearing headphones actually makes it much easier for other people to hear you. This is because when you don’t have them on, your computer or phone has to do a lot of extra work to cancel out the sounds of the other people coming through your speakers which would otherwise make an echo. The little bits of leftover cancelled echos interfere with the sound of your outgoing voice. That’s what makes people sometimes get a lot quieter for a few seconds — the echo cancellation is interfering with their voice.

So for the best experience, you really need to wear headphones. But alas, we just don’t yet have headphones comfortable enough to wear all day. And that brings me to Bluetooth.

Those Airpods that make you look cool also add 100 milliseconds of extra delay to every call. Brutal. See the six-second rule above — they almost certainly put you over the limit. And they make you sound like crap, too, since the microphone is jammed up against the speakers and therefore has to use hardware echo cancellation (see above). Finally, and this is the big frustration for our company because we are trying to add spatial audio to communication, the Bluetooth headphones don’t allow you to hear stereo when the microphone is in use. This means that, for now at least, we can’t spatialize the sound on a call that is using them.

The fix: Don’t use bluetooth until the next version comes out and addresses these problems as well as provides lower latency. Use comfortable headphones instead, or those simple wired earbuds that came with your phone.

There are solutions that address these issues — virtual spaces that don’t force people into small boxes, sans video, where you can move around naturally as you would at a real life gathering. Spaces that have both low latency and spatial audio to communicate naturally with one another.

We’ve also now released a Spatial Audio API, too, so apps and games can utilize audio technology that allows for better human conversations. Create your free developer account below to try it out.

Related Article:

by Ashleigh Harris

Chief Marketing Officer

There are countless articles, tweets, and LinkedIn posts from marketers and others expounding upon the future of virtual events and conferences; how ...

Subscribe now to be first to know what we're working on next.

By subscribing, you agree to the High Fidelity Terms of Service