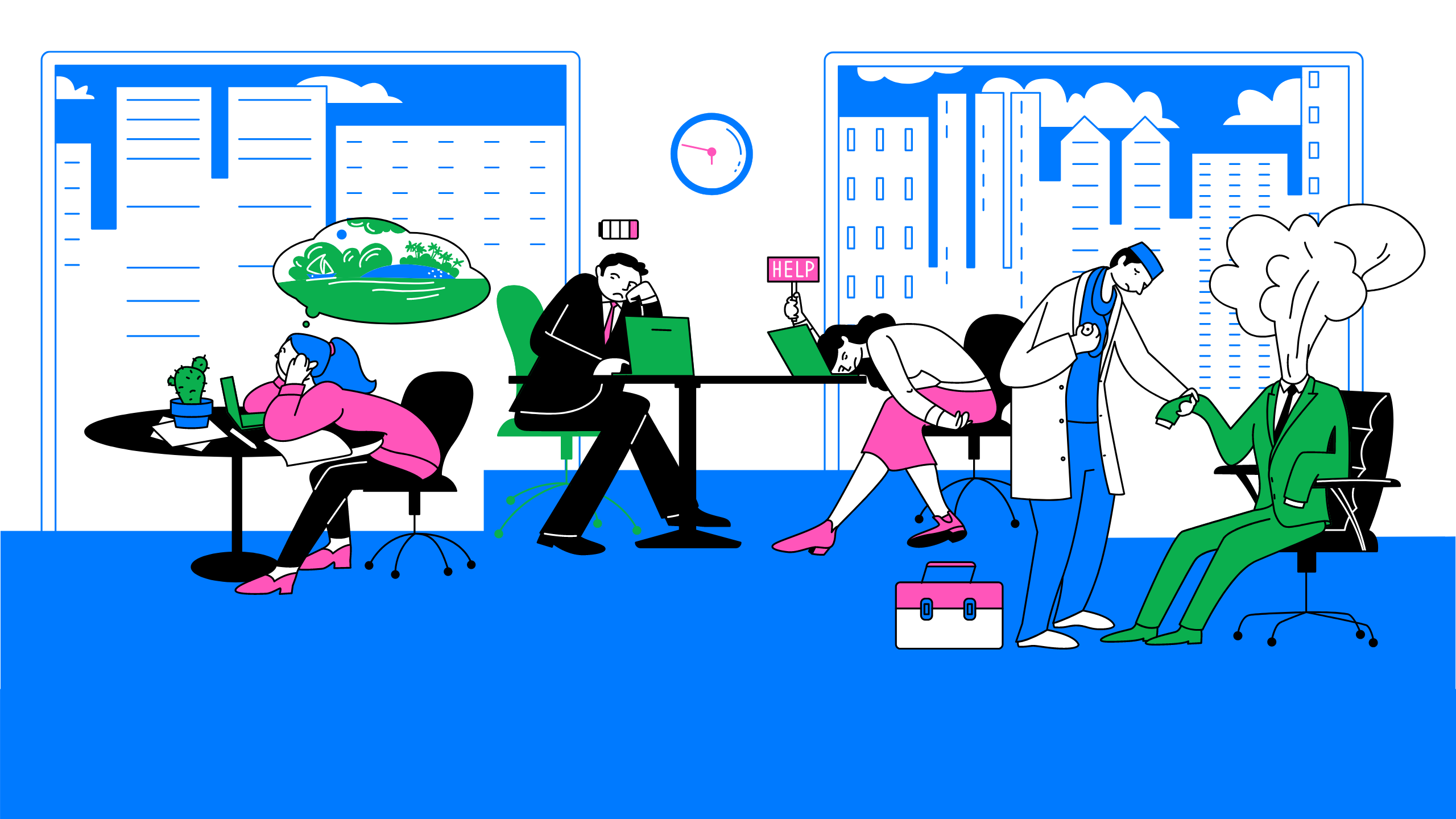

An Overlooked Solution For 'Virtual Event Fatigue'

There are countless articles, tweets, and LinkedIn posts from marketers and others expounding upon the future of virtual events and conferences; how ...

by Emily Iwankovitsch

Social Media Marketing Manager

Are you one of the 10 million weekly active users on Clubhouse who have listened in this past week? If so, you’ll notice a key difference — being able to more clearly understand the speakers on stage as they have a natural back-and-forth conversation. You feel as though you’re actually *in the room* with them, sitting at a dinner table all together.

How was this achieved? Clubhouse integrated High Fidelity's spatial audio to make conversations feel more natural and immersive.

And Clubhouse isn’t the only one: Skittish, a new playful space for online events, also uses spatial audio. “Many of the design decisions — no camera, spatial audio, animal avatars, the visual look of the space — were designed to get people comfortable interacting with others. From the moment you join, it’s clear this isn’t a meeting or conference call,” says Andy Baio, creator of Skittish.

Remote workers have certainly felt the need for this sort of more natural conversation this past year and a half, too. Tanya Basu writes for MIT Technology Review, “Indeed, many of the innovations in meeting technology over the past year have focused on re-creating the ‘water cooler’ moments that help employees bond. These low-stakes conversations (about weather or sports or TV, perhaps) are crucial to creating a sense of trust and perspective for future problem-solving. But those interactions require a sense of connection — one that Zoom boxes aren’t conducive to creating.” Proximity chat platforms and social audio apps are two important components of that — it’s clear there’s a future there.

I can't stop thinking about Clubhouse's spatial audio feature. This is going to be game-changing for video calls.

— Ian Woodfill (@IanWoodfill) September 7, 2021

All my video calls seem so 1 dimensional right now; this would totally help with Zoom fatigue. https://t.co/wugONsre7S

So how does “spatial audio” work to reduce negative effects of virtual communication? Let’s go over some great research.

First, a quick summary of the research: Spatial audio improves speech intelligibility while reducing cognitive load. Now we’ll break that down into more easily understandable terms.

“Speech intelligibility” is defined as how clearly a person speaks so that his or her speech is comprehensible to a listener. “Reduced speech intelligibility leads to misunderstanding, frustration, and loss of interest by communication partners.”

(We’ve already discussed some cool research on why audio-only interactions are easier to comprehend than those with video in another article. Here, we’ll focus specifically on spatial audio.)

During the experiment, people had to report the speech emitted by a “target” talker in the presence of a concurrent “masker” talker. Imagine you are standing at a party, chatting with another person. There are people around you chatting simultaneously (“masker” talkers). The ability to focus your attention on the person you’re speaking with, while filtering out others, is called the “cocktail party effect.” So in the research, Guillaume Andéol et al. investigated what conditions made it easier for people to understand each other in this sort of scenario.

Guillaume Andéol et al. writes, “Previous studies (reviewed in Bronkhorst, 2015) have found that two cues are particularly important: the voice frequency characteristics and the spatial separation between talkers. The most favorable voice characteristic condition is reached when the target and the masker have different genders. Likewise, higher intelligibility can be attained when the target and the masker are spatially separate.”

“Spatially separate” means that the voices are coming from different locations in space. How does High Fidelity’s Local Spatializer handle that for Clubhouse? Ken Cooke, principal audio engineer at High Fidelity, says: “Our HRTF filters continuously interpolate to avoid artifacts when sound sources move. We handle the extreme dynamic range of many people talking at once (or right into your ear) without distortion. And finally, the algorithms have been optimized to preserve battery life on mobile devices.”

Then, Andéol et al. looked at “cognitive processing load” (assessed by a prefrontal functional near-infrared spectroscopy), meaning: How taxing is an activity on our brains?

First, briefly recall Jeremy Bailenson’s research on Zoom fatigue includes increased cognitive load from using video in a virtual meeting. “Participants in the video condition made more mistakes on the secondary task than in the audio condition. In explaining the reason for the increased load from video, Hinds argues that dedicating cognitive resources to managing the various technological aspects of a videoconference is a likely cause, for example, image and audio latency. On Zoom, one source of load relates to sending extra cues. Users are forced to consciously monitor nonverbal behavior and to send cues to others that are intentionally generated. Examples include centering oneself in the camera’s field of view, nodding in an exaggerated way for a few extra seconds to signal agreement, or looking directly into the camera (as opposed to the faces on the screen) to try and make direct eye contact when speaking. This constant monitoring of behavior adds up.”

Indeed, it does.

And when Guillaume Andéol et al. looked at cognitive load, they found “Spatial separation can dramatically improve speech intelligibility without increasing the cognitive load. In fact, the spatial separation can even decrease the cognitive load for [specifically] the intermediate target-masker-ratio (TMR). The cognitive resources of listeners can often be limited in everyday life situations, either by age or pathology or when task demands exceed the listener's mental capacity — for instance, in a multitasking environment. Moreover, those same people can also suffer from low speech intelligibility because of weak or no access to spatial cues.”

Janto Skowronek and Alexander Raake found the same in their research when assessing cognitive load, speech communication quality, and quality of experience for spatial and non-spatial audio conferencing calls. “Spatial audio reproduction, i.e. system properties, can reduce cognitive load,” they write.

Spatial audio is important.

The best part of all this? It’s now possible to add spatial audio to native apps (such as Clubhouse). High Fidelity’s spatial audio solutions works with your existing audio pipeline. Each audio stream is automatically spatialized and can work with your existing user interface. Curious to learn more?

Taylor Hatmaker describes Clubhouse’s spatial audio experience: “While Clubhouse and other voice chat apps bring people together in virtual social settings, the audio generally sounds relatively flat, like it’s emanating from a single central location. But at the in-person gatherings Clubhouse is meant to simulate, you’d be hearing audio from all around the room, from the left and right of a stage to the various locations in the audience where speakers might ask their questions.”

Virtual communication is only going to continue to increase — whether it’s in social audio apps, virtual conferences, digital networking events, or videoconferencing, spatial audio is one way to improve conversation between humans.

Related Article:

by Ashleigh Harris

Chief Marketing Officer

There are countless articles, tweets, and LinkedIn posts from marketers and others expounding upon the future of virtual events and conferences; how ...

Subscribe now to be first to know what we're working on next.

By subscribing, you agree to the High Fidelity Terms of Service